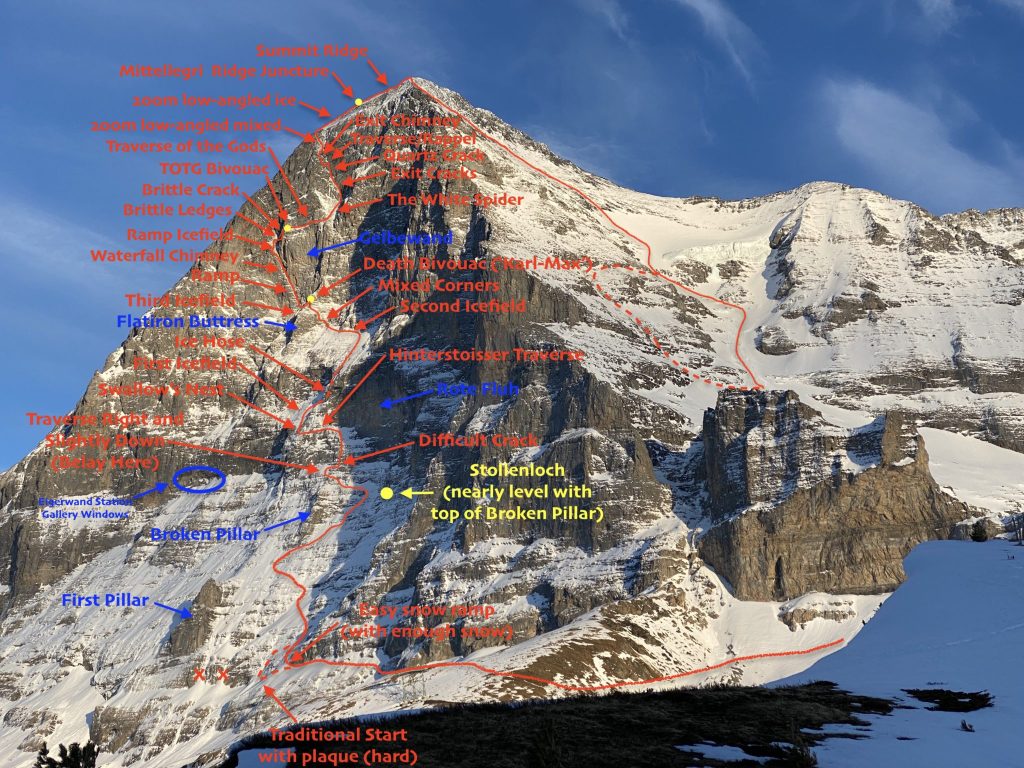

From now on, you can replace the phrase “calling a Kotlin suspend function” with “using the Stollenloch door”.

Introduction: imagine the Bernese Alps

Bear with me, here are some pictures to distract u make it easier.

This is an image of the Alps:

This is an image of the Bernese Alps, where the big mountains include the Jungfrau; Mönch, and Eiger (to the south of Lauterbrunnen):

This is the Stollenloch door, a wooden door on a hole drilled in the rock, made when the Swiss built the train track1 that goes up to the Jungfraujoch observatory:

This is where the Stollenloch door opens on the other side (yellow arrow):

Suspend is like the Stollenloch door

Back in the realm of Kotlin, when you first encounter a suspend keyword decorating a function call, you might think: “oh that’s nice, they are informing me that there may be multithreading here”. Actually, it’s not just a cute information-type annotation. If you try to call the function directly from normal blocking code, the Kotlin compiler will yell at you and tell you that you cannot pass this suspend threshold without your special gear (a.k.a. the compiler error « Suspend function can only be called from a coroutine or another suspend function »).

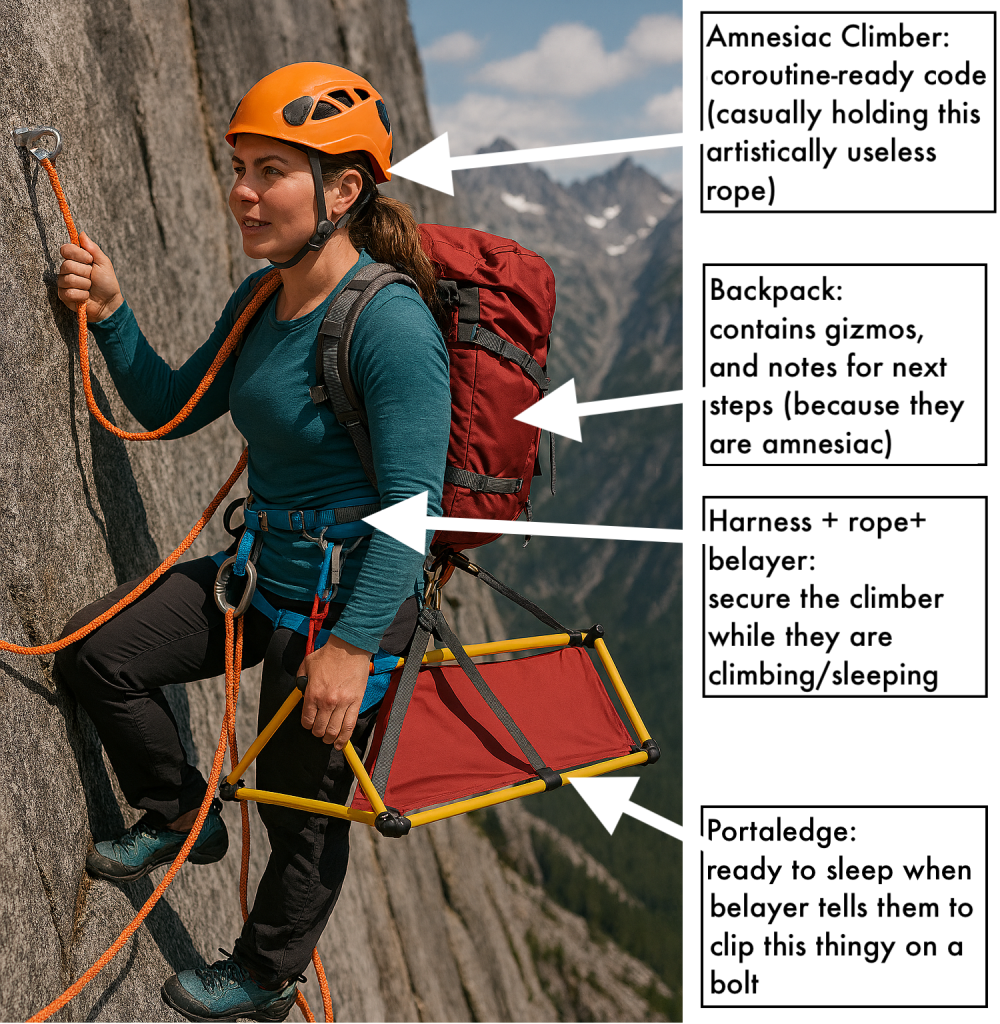

Because, actually, the suspend keyword is like the Stollenloch door on the Eiger mountain north face. When you pass its threshold, you need to already have your rope, harness and special gear backpack, because you are stepping out on a ledge on a sheer rock face, where you may need to sleep on a portaledge and keep notes of what your next step is (because it turns out you’re also an amnesiac).

Yes, that was the introduction. Moving on.

How Kotlin coroutines are like being an amnesiac climber

An illustration of our climber

Please ignore this unfortunate detail chosen by Copilot, who otherwise did a great job. Thanks Copilot!)

| Climber gear | Coroutine equivalent |

| Harness + rope + belayer | CoroutineScope: this ties our coroutine into a context and overarching lifecycle, so that they do not get lost in the wild, and can be cancelled if needed |

| Backpack 🎒 | Continuation object (putting the « C » in « CPS »): this object contains all the logic and context info needed by the climber-coroutine |

| Portaledge (a suspended sleeping cot used by climbers) | State machine generated by the compiler in the coroutine code, which allows the coroutine code to be paused (put to sleep) and retstarted (awoken) |

A metaphor for Kotlin coroutines

In order to pass the Stollenloch door and use suspend functions, you need to « gear up » 🎒. This is done by calling one of the « coroutine builders », which act as a portal between the flat (« bocking ») world into the « suspending world » of coroutines.

Kotlin programs without coroutines: just regular blocking code

When developing an application with Kotlin (Android or not), by default it is not running in a “coroutine context”. Your code will execute synchronously, meaning it will run on the calling thread (usually Main, the UI thread) only, and block that thread from doing any other work. In order to use coroutines, you must do so explicitly via “coroutine builders” (and eventually scopes and dispatchers).

Kotlin coroutines

Although coroutines rely on core Kotlin language and compiler features to work (the suspend keyword, Continuation object and transformation), you also need to add a library (kotlinx-coroutines) to your project in order to fully use them. The library provides higher-level constructs (coroutine builders, flows, scopes, dispatchers) on top of the core language concepts.

Confusingly, the “coroutine” itself is not visible as a class or something you manipulate directly, unlike what you have with Java Threads and the Runnable interface. Kotlin coroutines are pretty elusive (by design) in Kotlin code, and the single visible element, the suspend keyword, hides a good bit of important plumbing that is set up by the Kotlin compiler. Coroutines are represented internally by a Job object, but as a Kotlin developer you barely ever need to work with it. The developer mostly manipulates the coroutine builders (launch, async, runBlocking), existing and custom suspend functions, CoroutineScope, and CoroutineScope methods which change the state of the coroutine : cancel, join, await.

Kotlin coroutines are designed with CPS code: Continuation-Passing Style. The compiler crafts a Continuation-type parameter which is added to all functions that have the suspend keyword.

Within the Continuation object, there is a reference to a CoroutineContext object, which is instrumental to how structured concurrency works.

Structured concurrency means ensuring that every coroutine is owned by some scope and cannot escape its lifetime; functions that launch coroutines must wait for them or cancel them before returning.

What is the climbers backpack 🎒… I mean CPS (Continuation-Passing Style)?

CPS code means that the functions don’t return values, instead they are passed a parameter (a Continuation callback) which is called with the result once it’s ready.

The idea of coroutines is to have a block of code that can pause and resume execution. When pausing, the current state of the block is captured in the Continuation object, which can be simply serialized to store for later. The paused coroutine no longer needs a Thread. Execution is resumed by invoking the methods of the Continuation object.

Kotlin compiles suspending functions by transforming them into CPS code. Each suspend function is transformed to accept a Continuation<T> parameter, which includes:

resume(value: T)— resumes with a resultresumeWithException(e)— resumes with an error

The Continuation object is obtained by calling suspendCoroutine

This allows Kotlin to pause execution (e.g., during network calls) and resume later without blocking threads

But when you are writing code, you do not see the Continuation boilerplate code, because it is added in by the compiler. The developer can write simple sequential code lile this:

suspend fun getValue(parameter: String): MyValue {

val resultA = makeAsynchronousCall() // suspension point while asynchronous call is executed

val resultB = makeOtherAsynchronousCall() // suspension point while asynchronous call is executed

return resultA + resultB // resume once results have been obtained

}Written like this, the developer can ignore the implicit Future / Promise / callback that needs to happen for this code to be paused while waiting for the result from the asynchronous call. The compiler transcribes this into something like this (Java pseudo-code):

public final Object getValue(parameter: String, Continuation<MyValue> continuation) {

switch (continuation.label) {

case 0: // Initial state

continuation.label = 1; // change label to next state

if (makeAsynchronousCall() == COROUTINE_SUSPENDED) return COROUTINE_SUSPENDED;

break;

case 1: // State 1: execution resumes here after the makeAsynchronousCall call returns

continuation.label = 2; // change label to next state

if (makeOtherAsynchronousCall() == COROUTINE_SUSPENDED) return COROUTINE_SUSPENDED;

break;

case 2: // Final state: execution resumes here after the makeOtherAsynchronousCall call returns

break;

default:

throw new IllegalStateException(message);

}

return someValue;

} This implementation defines a state machine (based on the value on the Continuation.label attribute) separating the steps of execution. This allows each step of the coroutine to be called sequentially, always saving the state reached before returning. The Dispatcher can save this value and suspend it for now. The repeated calls to this method are triggered when the secondary calls (« makeAsynchronousCall », « makeOtherAsynchronousCall » in this example) finish execution. The final execution calls one of Continuation’s resume methods in order to return the result to the caller of getValue, like a callback.

Back to our metaphor

So, as we’ve seen, Kotlin coroutines involve some gear that you need to acquire before jumping into any suspend function call.

- The CoroutineScope is the harness. It holds metadata securing the coroutine execution in a structured concurrency ensemble: dispatcher, job, name, as well as the tree of context and lifecycle.

- The backpack is the Continuation object. It holds resume logic and context.

- The portaledge is the state machine in the coroutine code => when deployed (suspended), the climber is sleeping on the portaledge, securely clipped to a bolt, and not using any belayer’s attention. When it is not deployed: the climber is progressing on their route (executing the next step of the coroutine code), supervised by a belayer.

The suspend keyword is the warning sign at the ledge onto the wall: « This route is a dangerous cliff requiring a harness (CoroutineScope), backpack (Continuation), and a portaledge (state machine). » Without it, you cannot enter this path.

The belayer crew will keep you secure and let you know when you need to wait, and when to resume, and it will keep an eye on whether you are still alive.

The belayer crew may be handling multiple climbers like yourself at the same time. When the climber is climbing and gets to an anchor point, the suspend gizmo tells them to stop there and go to sleep on the portaledge. The climber is awoken by the resume alarm clock.

But the climber wakes up being disoriented, and doesn’t remember what they were doing, so they need to look in their backpack where their route map is (the Continuation backpack). Alternatively, they may be awakened with an exception message, and they need to decide whether to backtrack, change route, or do something else.

Step-by-step flow

| The future climber gears up by getting a CoroutineScope and calling a coroutine builder; these are their harness and rope + belayer |

| Climber enters the Eiger north face via suspend fun gate, wearing a harness and gets a Continuation backpack |

| Climber reaches anchor point (suspension like delay() or withContext()): she clips suspend gizmo → auto-deploys portaledge, packs current position/route notes into backpack → falls asleep (suspends). Belayer crew (thread/dispatcher) focuses on other climbers. |

| Resume alarm (normal completion): wakes climber. Amnesiac climber unzips backpack to check what Continuation has listed for next steps → « Oh right, route continues that way » |

| (no image due to possibly violent content) | Exception alarm (failure): wakes with red flag. Climber checks backpack for contingencies (« try this alternate route » or « rappel to last safe ledge ») → handles via catch logic or propagates cancellation down. |

- Note: Please note that the Swiss trains of the Jungfraubahn no longer stop at the Eigerwand station to let mountaineers climb on the Eiger north face from there, sorry. ↩︎